The Case for Mindfulness and Voice

As a singer, voice instructor, and mindfulness teacher with a voice disorder, I am passionate about helping people optimize their voices and reduce stress. People with voice disorders often experience high stress levels; social and emotional isolation; and loss, including loss of work opportunities, sense of self, and the ability to communicate.

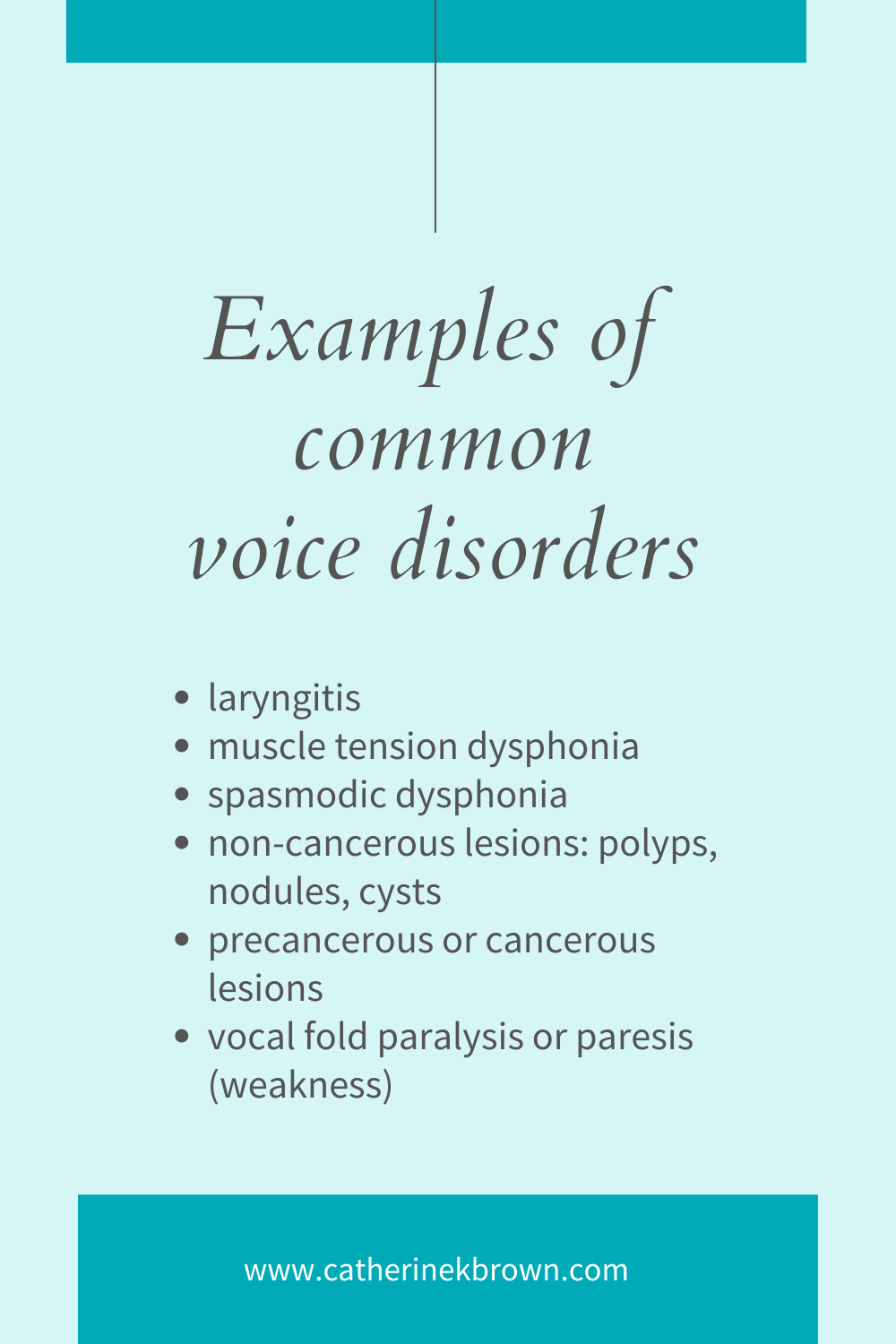

What is a voice disorder? According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, “A voice disorder occurs when voice quality, pitch, and loudness differ or are inappropriate for an individual’s age, gender, cultural background, or geographic location.” Examples of common voice disorders include laryngitis; muscle tension dysphonia; spasmodic dysphonia; non-cancerous lesions: vocal polyps, vocal nodules, vocal cysts; precancerous or cancerous lesions; and vocal fold (vocal cord) paresis (weakness) or paralysis.

Nearly every modern textbook on vocal pedagogy, vocal health, or the causes and treatment of voice disorders recommends stress reduction as both a preventive and therapeutic tool for voice users and patients with voice disorders. Many specifically mention meditation and yoga, with occasional references to Jon Kabat-Zinn and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Any benefits of mindfulness meditation that are cited typically come from studies that do not directly involve voice use, as there are no published studies directly testing the effects of Mindfulness Based Interventions (MBIs) in people with voice disorders.

Despite the dearth of research, there are many reasons to think that structured mindfulness interventions would be helpful for this population. Many people turn to mindfulness in times of personal crisis. They may seek out a meditation class following the loss of a loved one, a cancer diagnosis, the onset of a stress-related illness, or as a tool to manage chronic pain, depression, or anxiety.

In their book Psychology of Voice Disorders (2nd ed.), Deborah C. Rosen and Robert T. Sataloff (2021, p. 364) maintain that being diagnosed with a voice disorder is indeed a personal crisis, particularly for professional voice users. It is a time of high stress and deep grief — and may be accompanied by anxiety and depression.

Stress can play a complex role in voice disorders. It can be both a causative factor — as in psychogenic voice disorders where there is no underlying physical problem — or an exacerbating factor, worsening the disorder itself and impeding treatment (Rosen et al, 2021, p. 3). The diagnosis and treatment of voice disorders may include invasive testing, injections, dietary changes, medication, surgery, and an intensive regimen of voice therapy with at-home exercises. In addition, the voice disorder itself can be a source of stress, particularly in patients who use their voices to earn a living.

According to Rosen et al. (2021), “In one study of all new patients with voice concerns, it was observed that one-third had clinically significant psychosocial distress (depression, anxiety, etc.) and about one-half had high-risk scores for distress, although most reported no prior mental health diagnosis. (Misono et al., 2014) Levels of distress were comparable to that of newly diagnosed cancer patients in outpatient cancer care clinics (Stefanek et al., 1987; Kwak et al., 2013), reflecting the significant impact voice disorders can have on well-being.” (p. 163)

In their essay “Mindfulness: A Transtherapeutic Approach for Transdiagnostic Mental Processes,” Greeson et al (2014) argue compellingly that “mindfulness can target core cognitive, emotional, neural, physiological, and behavioral processes implicated in the risk, severity, and relapse of mental disorders.” Mindfulness, they write, can help people deal with negative affectivity and emotional reactivity (associated with depression and substance abuse), repetitive negative thought (depression, anxiety, addiction, insomnia), experiential avoidance (depression, anxiety, PTSD, eating disorders, addiction, chronic pain), attentional bias (mood disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, chronic pain, addiction), and suppression (PTSD, addiction, OCD). Additionally, mindfulness encourages reappraisal, a process by which we give meaning to adverse events (Greeson et al, 2014). This is particularly important for people with voice disorders because, as Rosen et al write, “[I]t is not the [vocal] disability per se that psychologically influences the person, but rather the subjective meaning and feelings attached to the disability” (Rosen et al, 2021, p. 213).

People with voice disorders often experience feelings of grief and loss around their vocal limitations. These are heightened even further in professional voice users, who may also experience loss of professional and personal identity, income, and career (Rosen et al, 2021, pp. 363-367). Many patients, particularly those with severe voice problems, do not know anyone else with similar struggles. Group therapy can be particularly helpful for patients with voice disorders. “Participants benefit from the perspective and progress of other patients, the opportunity to decrease their experience of isolation, and the sharing of resources.” (Rosen et al, 2021, p. 324)

I believe that people with voice disorders could experience similar benefits from the group experience provided by a structured mindfulness course specifically for patients with voice disorders. We know that the group aspect of MBSR classes is particularly powerful. In their article “Beyond the individual: group effects in mindfulness-based stress reduction,” Imel et al attempted to measure the effect of the group on MBSR outcomes. They found that the group itself accounted for 7% of the variability in psychological symptoms. (“A commonly reported estimate of therapist influence on psychotherapy outcome is 5%” [Wampold & Brown, 2005, as cited in Imel, 2008].)

The Study: The Effects of an 8-Week Mindfulness Course in People with Voice Disorders

Before my study, no research had been conducted of MBSR-style interventions in people with voice disorders. However, some similar somatic, body-based disciplines are commonly used by acting voice coaches and among singers. Many acting voice teachers are trained in the Alexander technique, the Feldenkrais method, and the voice work of Arthur Lessac, Kristin Linklater, and Catherine Fitzmaurice. Speech language pathologists who specialize in voice are frequently trained in one or more of these methods, as well as in circumlaryngeal manual therapy (CMT), a form of massage focused on the muscles around the larynx.

Yoga, an essential component of mindfulness-based interventions, has become increasingly popular among singers and singing voice teachers. Somatic reeducation and embodiment are particularly important for speech language pathologists treating muscle tension dysphonia (MTD), a voice disorder characterized by significant tension of the laryngeal musculature. MTD can be caused by “(1) psychological and/or personality factors, (2) vocal misuse and abuse, and (3) compensation for underlying disease.” (Van Houtte et al, 2011) It is one of the most common voice disorders and may occur following an illness or in conjunction with another voice disorder.

My research, which has been published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Voice, involved studying the effects of mindfulness on people — both speakers and singers — with voice disorders. Participants took part in an 8-week mindfulness course, modeled after the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) curriculum, which was delivered over Zoom. The class included yoga sequences specifically designed to target places where people with voice disorders hold tension. Before and after the 8-week course, I measured all subjects’ mindful awareness using the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), stress using the Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10), and degree of voice handicap. I used two different tools to measure voice handicap. Everyone took the Voice Handicap Index (VHI), and singers also took the singer-specific Singing Voice Handicap Index (SVHI).

Everyone involved in the study filled out the measurement tools before and after an 8-week time period. Those in the mindfulness group took the 8-week course and those in the waitlist control group were offered the course after the 8-week waiting period. When we compared the mindfulness course participants to themselves before and after the mindfulness course, all outcomes changed significantly in the direction hypothesized. (In other words, mindfulness scores went up, and stress and vocal handicap scores went down.)

When we compared the changes in the mindfulness course participants to the changes in the waitlist control group, two outcomes changed significantly in the direction hypothesized: the mindfulness scores and the voice handicap scores. (Changes to the stress scores and singing voice scores were not statistically significant.)

In follow-up interviews, participants expressed experiencing:

increased somatic awareness (“My biggest takeaway is noticing when I start to feel tense.”)

reduced physical tension (“The overall level of physical tension has definitely gone down.”)

fewer vocal symptoms (“I noticed a stronger voice and also fewer spasms and greater vocal clarity.” “It was easier to sing. I was able to sing high notes.” “I started to feel a greater sense of control in the voice.”)

increased confidence while speaking (“My voice just sounds a little more confident.”)

increased acceptance of their disorder (“Mindfulness helped me feel more accepting of having the disorder.”)

Conclusions

We suspect somatic (or interoceptive) awareness may play a larger role than stress reduction in vocal improvement.

Certain patients — those with moderate to severe VHI scores — seemed to benefit most. (The study is too small to draw statistically significant conclusions.)

Several patients with dramatic drops in VHI (for example 20-30% decreases) had muscle tension dysphonia. (The study is too small to draw statistically significant conclusions.)

Patients with spasmodic dysphonia seemed to benefit less vocally, but frequently expressed gratitude for the chance to hear and talk to other SD patients. Many also expressed increased acceptance of the disorder.

Participants repeatedly expressed that they had no support system when they were discharged from voice therapy. Many felt they had failed therapy because they continued to experience voice problems after discharge. The mindfulness course may have helped address some of the physical manifestations of the disorder (tension and pain), while also addressing the psychological fallout (loss, grief, isolation, and anxiety/embarrassment about the disordered voice).

Some participants did not see any vocal benefit from the mindfulness course.

Mindfulness Classes and Downloads

I now offer online classes that use the curriculum that I tested in my study: http://www.mindfulvoicecollaborative.com/classes

You can also purchase the meditations used in the study: http://www.mindfulvoicecollaborative.com/store

Blog post originally published in 2022. Revised in April 2024.

REFERENCES

Greeson, J., Garland, E. L., & Black, D. (2014). Mindfulness: A Transtherapeutic Approach for Transdiagnostic Mental Processes. In The Wiley Blackwell handbook of mindfulness (pp. 534–562). essay, Wiley Blackwell.

Imel, Z., Baldwin, S., Bonus, K., & Maccoon, D. (2008). Beyond the individual: group effects in mindfulness-based stress reduction. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 18(6), 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802326038

Kwak, M., Zebrack, B. J., Meeske, K. A., Embry, L., Aguilar, C., Block, R., Hayes-Lattin, B., Li, Y., Butler, M., & Cole, S. (2013). Trajectories of Psychological Distress in Adolescent and Young Adult Patients with Cancer: A 1-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31(17), 2160–2166. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2012.45.9222

Rosen, D. C., Sataloff, J. B., & Sataloff, R. T. (2021). Psychology of voice disorders. Plural Publishing, Inc.

Stefanek, M. E., Derogatis, L. P., & Shaw, A. (1987). Psychological distress among oncology outpatients. Psychosomatics, 28(10), 530–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0033-3182(87)72467-0

Van Houtte, E., Van Lierde, K., & Claeys, S. (2011). Pathophysiology and Treatment of Muscle Tension Dysphonia: A Review of the Current Knowledge. Journal of Voice, 25(2), 202–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2009.10.009